GDP-B: Measuring Well-Being

A new measure of wealth and growth in a digital economy

We propose a new method to measure modern economies.

There is concern that the wedge between measured GDP and implied consumer welfare is increasing over time. We are ultimately interested in people’s well-being–making it more pertinent than ever to get a better measure of consumer welfare.

The trouble with GDP

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is the sum of the value of all goods and services produced in a country in one year, where price is a proxy for value.

Developed in the 1930s and reported quarterly, GDP remains the dominant metric economists and policymakers look to for analyzing the health of our economy and setting economic policy.

But as a measure of market-based production and consumption, GDP does not account for most aspects that make life worth living. It also excludes volunteering and work done at home that is not paid for with money, including caring for children and the elderly.

The welfare of a nation can scarcely be inferred from a measure of national income.

GDP doesn’t measure up

People generally prefer better health, less environmental pollution, increased personal safety, more public parks and green spaces, fewer armed conflicts, safer roads and less traffic, high-quality cultural amenities, etc.

Yet, improvements in these areas often do not show up in GDP. Other welfare-decreasing events such as accidents, pollution, or natural disasters often even increase GDP due to spending on repairs and clean-up activities.

By accounting for a broader set of areas that influence people’s well-being now and in the future, we can provide a more comprehensive picture of our progress.

GDP is a measure designed for the twentieth-century economy of physical mass production, not for the modern economy of rapid innovation and intangible, increasingly digital, services.

A brand new perspective

GDP-B—the ‘B’ stands for benefits—measures how much consumers benefit from goods and services, not just how much they pay.

Our approach starts from basic principles of economics: changes in well-being stem from changes in the economic surplus created by goods and services, rather than the money spent on them.

While deeply rooted in economic theory, the empirical measurement of “consumer surplus” was often thought of as too challenging. However, recent advances in massive online experiments have made this possible for a larger number of goods.

What you measure affects what you do…If you don’t measure the right thing, you don’t do the right thing.

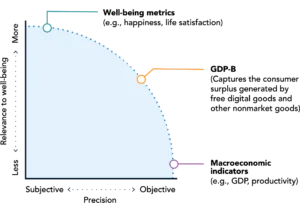

A dashboard of indicators

Macroeconomic indicators can be fairly precisely measured, but they tell only part of the story. Well-being metrics convey a truer picture of how consumers are doing, but they are more subjective. We believe that by considering an array of measures, including GDP-B, policy makers, regulators, and investors can establish a better foundation for decision-making.

What is the value of something you can consume for free?

The price of something is a significant factor in people’s consumption decisions. It is also the basis for how national accounts measure value creation. Yet, just because something is free in monetary terms does not mean it does not have value. In fact, often the opposite holds true.

For example, most of us derive value from nature or the environment more broadly, personal health, cultural amenities and heritage, as well as social interactions or connections. Our valuation methods allow us to start providing answers to how important all of these elements are for people’s overall well-being.

The outcome could revolutionize how we make policy decisions to maximize the well-being of current and future generations.

A proper measure of the sources of economic welfare is crucial as this affects decisions by governments, firms, and people. GDP-B measures consumer surplus, free digital goods, and sources of welfare.

Consumer surplus

We begin by considering consumer surplus, which measures the amount of welfare people derive from any kinds of consumption of products or services. This includes everything GDP measures, such as the coffee we buy on the way to work, the gas we put in our cars, the overseas trip for our next holiday, and the new TV we just bought.

Free digital goods

In addition, we consider the value people derive from using free digital goods such as Google Maps or Instagram, and our aim is to include more and more of those, especially the widely used ones.

Sources of welfare

Next, we acknowledge that people get lots of value from other things in life, including improved health, cleaner air and reduced pollution, or many aspects of work within the household, including caring for children or elderly. We also want to measure those sources of welfare and are working on surveys to capture them.

We envision GDP-B will become part of the key indicators policymakers look to to assess and benchmark the success of past policies or proposed solutions for the future.

Which digital products provide value to people and how does this differ across groups, urban and rural regions, and over time? This is particularly important given the fast appearance and spread of new digital tools which can be diggicult to track using conventional statistics.

We can provide new insights into people’s preferences regarding protection of environmental and natural assets such as clean air and water. We can also show how these change over time ro across groups: for example, in light of natural disasters.

Lower mortality and morbidity create massive welfare for people and yet go largely unnoticed by national statistics where input often equals output. This means we make suboptimal allocations of limited resources, for example, when it comes to preventative medicine. Asking people directly can provide valuable new insights and inform better decisions.

Creating new measures of value creation from scratch also provides the opportunity to take inequality seriously from the outjset. GDP is biased becasue it gives more weight to groups with higher purchasing power in the market. Yes, as we have seen, many things that provide value to people are outside the market.

Most activities that take place within households create a lot of value in an economic sense but they remain outside of GDP. THis is an issue because technology can affect what is considered inside as opposed to outside of the market we measure with GDP. Another issue is that becasue much of this activity is traditionally undertaken by women, their economic contribution may appear much smaller than it actually is.

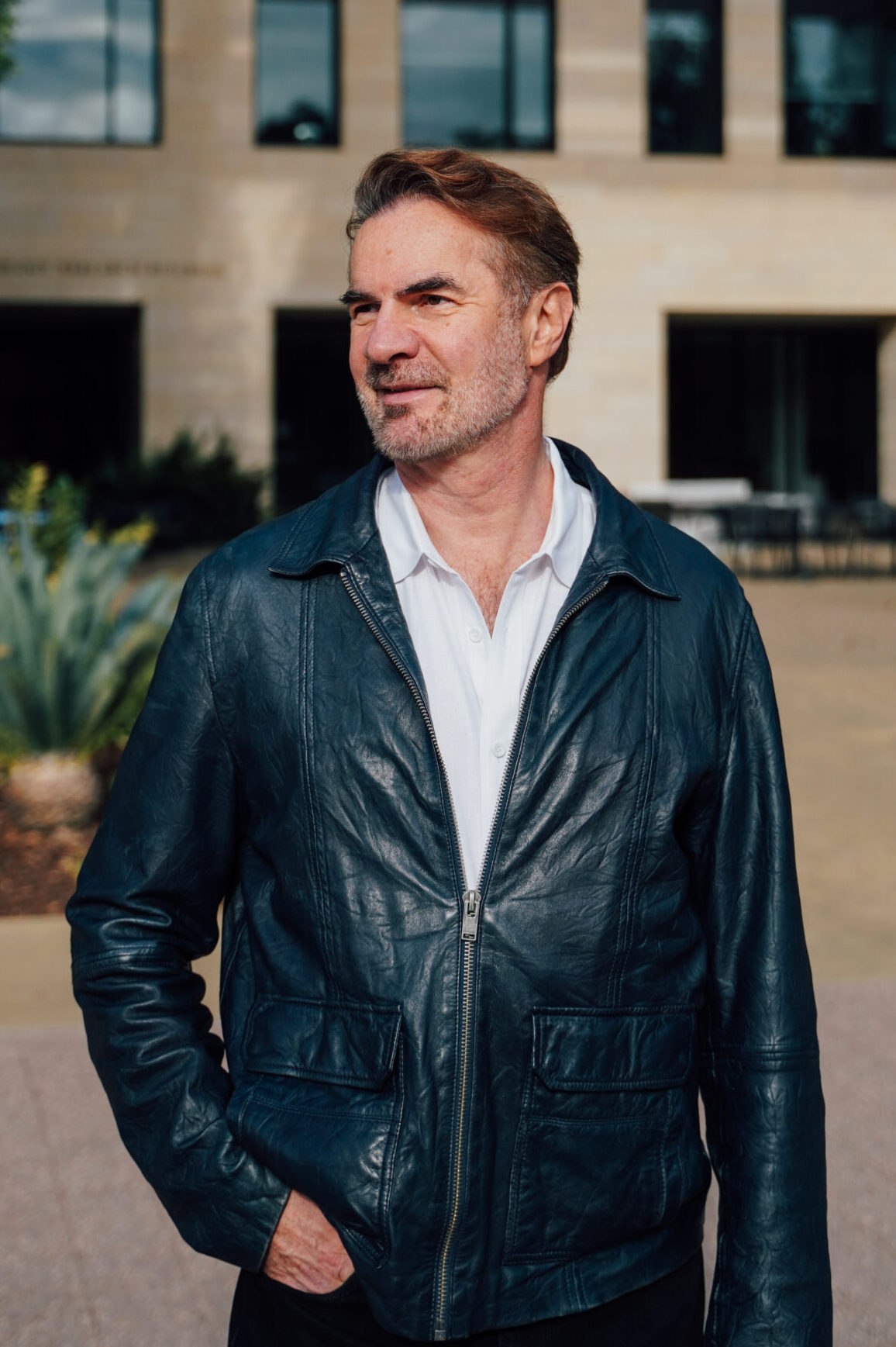

GDP-B Advisory Committee Members

Jason Liu

Founder, Digital Civilization Pte. and Chairman of Wonder Lake Capital

Paul Schreyer

Former Chief Statistician, OECD

Rachel Soloveichik

Research Economist, U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis

Leonard Nakamura

Emeritus Economist, Federal Reserve Bank Philadelphia

The Consumer Welfare Effects of Online Ads: Evidence from a Nine-Year Experiment

The Digital Welfare of Nations: New Measures of Welfare Gains and Inequality