Stanford Digital Economy Lab / February 9, 2026

Canaries, Interest Rates, and Timing: More on the Recent Drivers of Employment Changes for Young Workers

by Erik Brynjolfsson, Bharat Chandar, and Ruyu Chen

We’d like to highlight some key findings from our “Canaries in the Coal Mine” paper, which we last revised on November 13, 2025. In this note, we focus on two questions that have been increasingly discussed.

- Can the sharp changes in interest rates explain the employment effects we observed better than AI-exposure?

- Is the timing of the employment effects consistent with AI-exposure?

In brief, we find that:

- While interest rates affect overall employment, existing evidence does not suggest they are a good explanation for the disproportionate decline in entry-level hiring in AI-exposed occupations.

- On the timing, we do find suggestive evidence that when you include the broadest set of controls (firm-time fixed-effects), the timing of the employment decline in AI-exposed occupations becomes significant only in 2024; the earlier declines are likely (at least partly) due to some combination of other factors, not just AI.

The Effects of Interest Rates on Employment

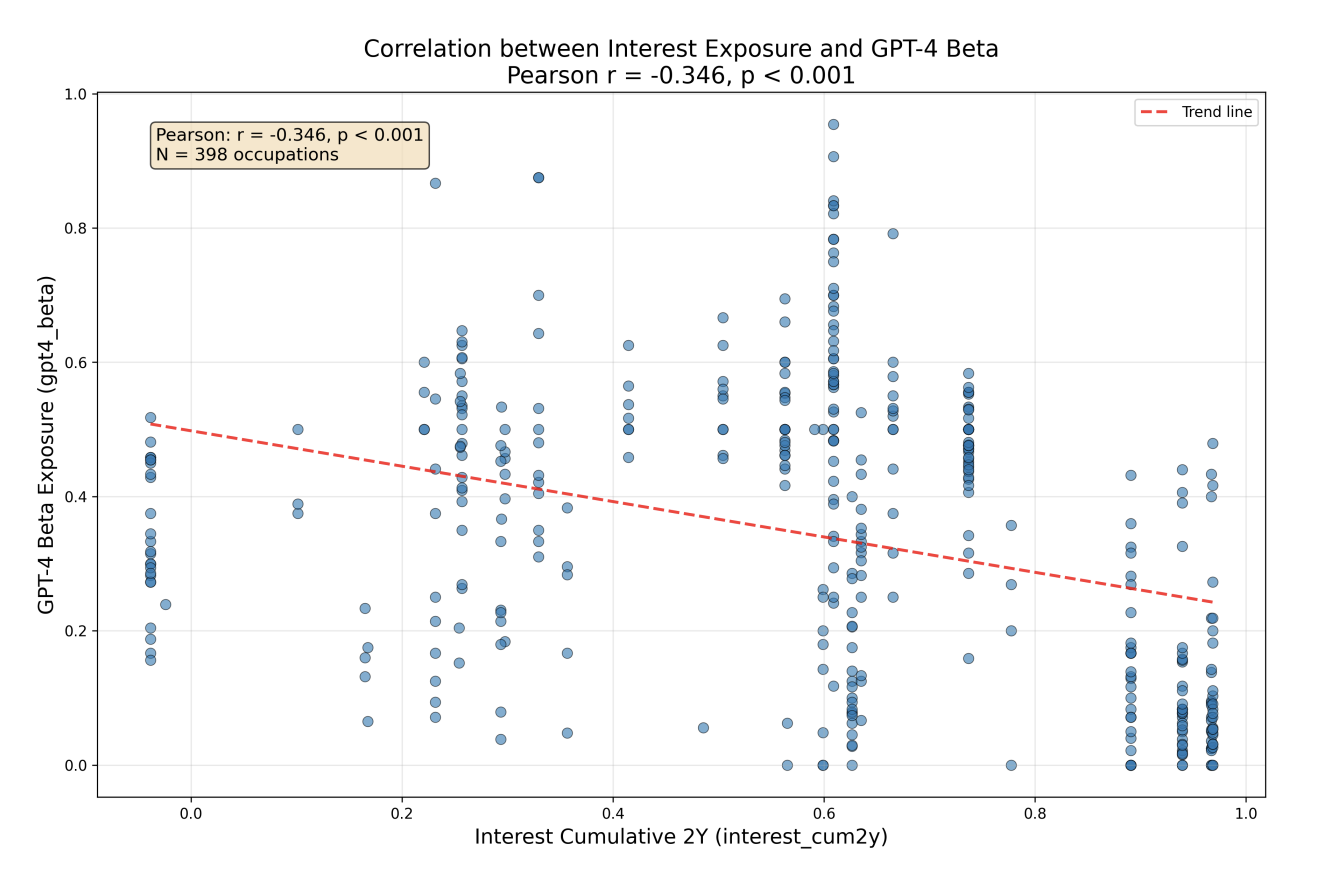

While it is true that interest rates affect overall employment, using data graciously shared by the authors of Zens et al. (2020), we find evidence that more AI-exposed jobs are actually less exposed to interest rates on average. See Figure A22 from our November paper, which plots AI exposure from Eloundou et al. (2024) against interest rate exposure.

For example, occupations such as construction have high interest rate exposure and low AI exposure.

A few points deserve mention. First, the available interest rate data do not have as much occupational granularity as the AI exposure data from Eloundou et al. (2024). Second, the Zens et al. (2020) estimates do not condition on age, and young workers may potentially have different occupational interest rate exposure than the workforce as a whole. While more research would help with further testing the interest rate channel, the existing evidence suggests the jobs that are most affected by AI are not the same as the jobs most exposed to interest rates.

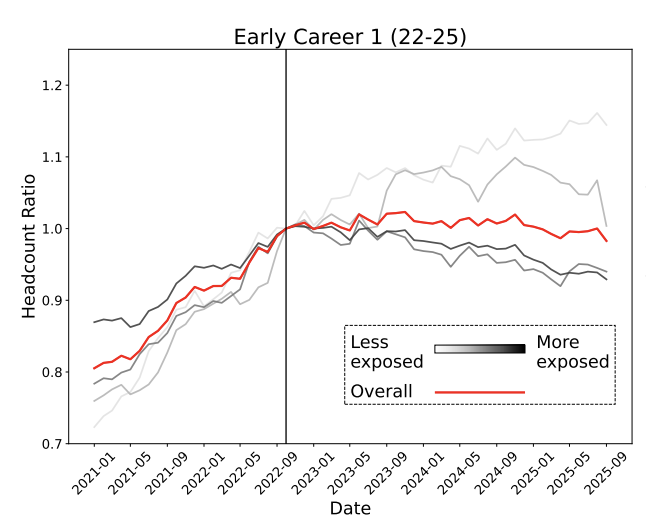

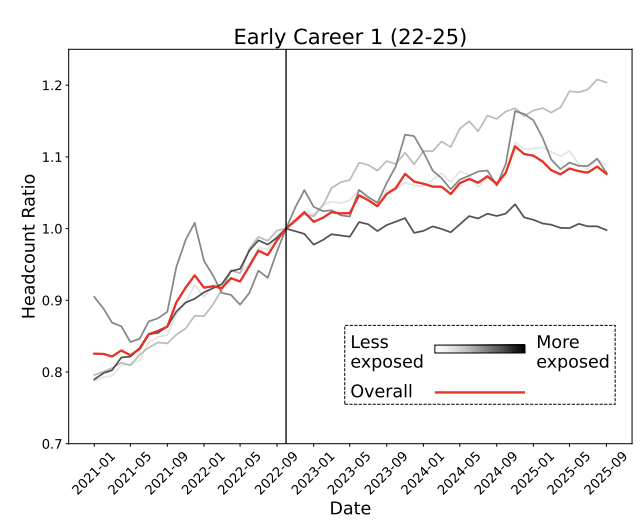

We compared employment trajectories for the jobs that are more or less exposed to interest rates. In both cases we found that the most AI-exposed occupations (darkest shade of gray) have greater declines in employment than the average occupation (red).

The Timing of Employment Declines in AI-Exposed Occupations

While these charts are suggestive of a relationship between AI and employment, we can’t be sure of the causality from this sort of analysis. As we noted in our November paper, and we now want to re-emphasize: we do not believe that AI is always and everywhere the sole determinant of employment, and we do not encourage others to interpret our results in that way. For example, the precipitous decline in employment for young software developers is a consequence of various factors. Even if employment outcomes diverge notably only after the release of ChatGPT, this could be driven by other changes that occurred at the same time.

In fact, there is reason to believe that part of the timing of this decline is due to factors other than AI. When we explore a more stringent approach to control for other factors, the employment decline is significant only after 2024.

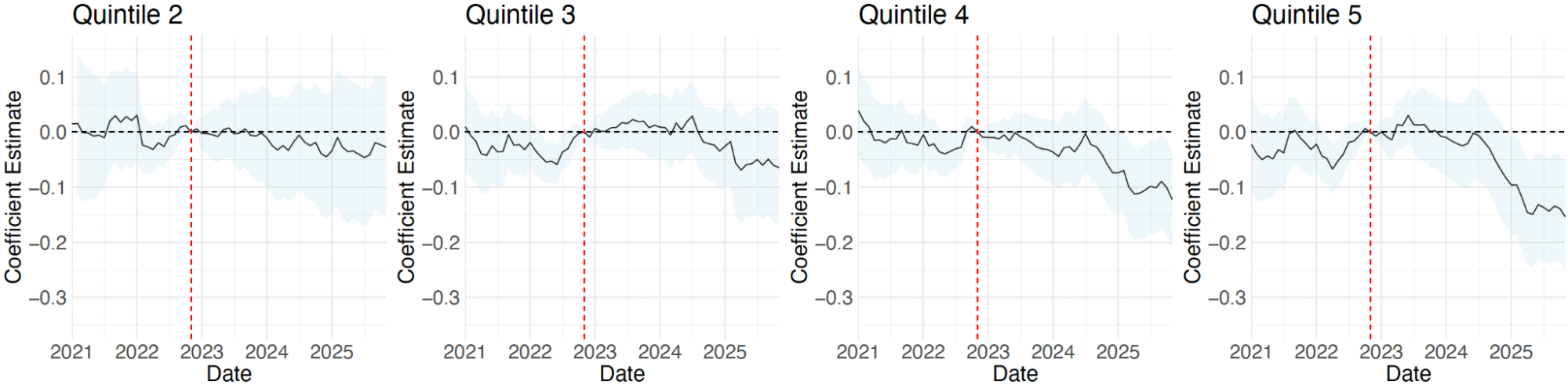

Specifically, one way to get a sense of the role of other macroeconomic factors compared to AI is to consider our results that control for overall changes in firm employment. In our regression analysis with firm-time effects, we find a relative decline in employment for the most-exposed young workers (quintile 5, and to some extent quintile 4 in Figure 3) that starts becoming notable in 2024 (not late 2022 or 2023 as in Figure 2).

Conclusion

Looking at the totality of the existing evidence, we do not find strong support for the hypothesis that interest rate changes explain the disproportionate decline in entry-level employment for AI-exposed occupations that we uncovered. However, we do find evidence that, once a broad set of other factors is controlled for, the relationship between AI-exposure and employment decline starts in 2024, not late 2022 or 2023. With the fixed-effect approach, the employment changes start later, but they are growing (reaching about 16% by October 2025, vs 13% in our paper with data only through July), and they have not shown a reversal. Given these trends, these employment changes bear close monitoring.

By now, there are several papers exploring the broad employment effects of AI, each using different data and methods, and thus subject to different strengths and weaknesses. In addition to our paper, we encourage those interested to take a look at the excellent work by Humlum and Vestergaard (2025), Hosseini and Lichtinger (2025), Gimbel et al. (2025), Klein Teeselink (2025), Frank et al. (2025), Azar et al. (2025), Liu et al. (2025), Chen and Stratton (2026), Iscenko and Curto Millet (2026), Klein Teeselink and Carey (2026), and many others, especially as they progress through the academic publication process. This essay by Bharat from October discusses some of these different results, though it is due for a refresh!

Since we don’t have an experiment where we can compare a world with AI to one without, this will remain an active area for scientific research and discussion. We will be actively monitoring the labor market and updating our results periodically to see if the trends we identified persist, strengthen, reverse, or change in some other ways.

About the authors

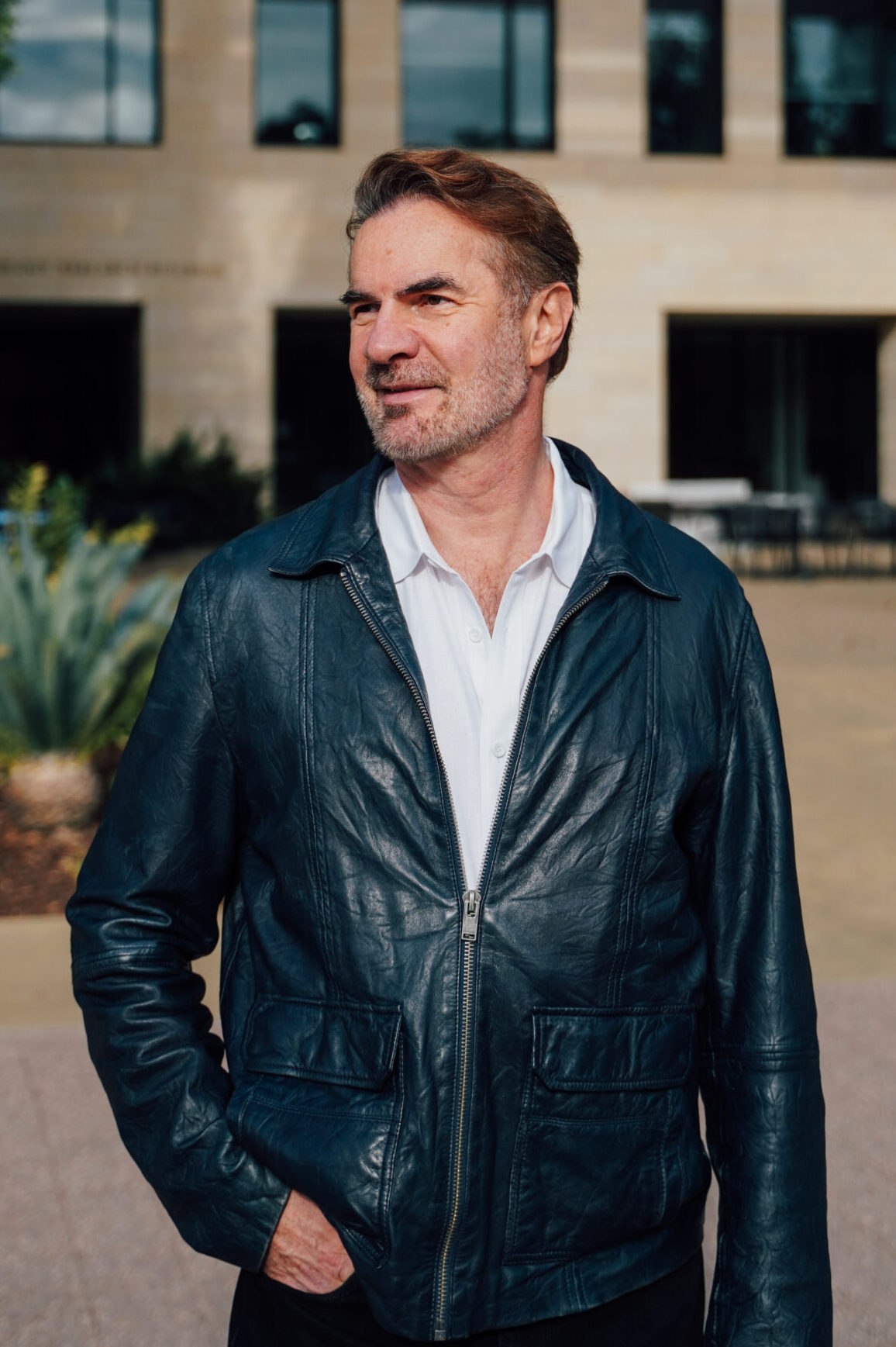

Erik Brynjolfsson

Jerry Yang and Akiko Yamazaki Professor

Erik Brynjolfsson is one of the world’s leading experts on the economics of technology and artificial intelligence. He is the Jerry Yang and Akiko Yamazaki Professor and Senior Fellow at the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered AI (HAI), and Director of the Stanford Digital Economy Lab. He also is the Ralph Landau Senior Fellow at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR), Professor by Courtesy at the Stanford Graduate School of Business and Stanford Department of Economics, and a Research Associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

One of the most-cited authors on the economics of information, Brynjolfsson was among the first researchers to measure productivity contributions of IT and the complementary role of organizational capital and other intangibles.

Read more

Bharat Chandar

Postdoctoral Fellow

Bharat Chandar is a labor economist working on understanding AI’s impact on work. His recent projects include work with Erik Brynjolfsson and Ruyu Chen tracking “canaries in the coal mine” for entry-level employment changes in jobs exposed to AI. He also recently surveyed the state of knowledge about AI and labor markets.

His ongoing work has focused on three areas. The first asks, how will workers adjust if we see AI-driven changes in hiring? Which workers will have an easier or more challenging time if displaced, and where should we target support? The second asks, how can we use AI to make it easier for people to learn new things and pursue new forms of work? Third, how will impacts of AI differ across the world?

Read more

Ruyu Chen

Research Scientist

Ruyu Chen is a research scientist at the Digital Economy Lab and the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (HAI). Her research lies at the intersection of the economics of innovation, information systems, and business strategy.

She focuses on two main areas: information technology adoption and firm performance, where she examines the drivers of IT adoption within firms and its impact on innovation and market performance; and AI and the future of work, where she leverages large-scale payroll data to study how emerging technologies, particularly generative AI, are reshaping employment, wages, skill demands, and organizational structures. Her work has been published in leading academic journals, including the Strategic Management Journal.

Read more

Canaries in the Coal Mine? Six Facts about the Recent Employment Effects of Artificial Intelligence

Erik Brynjolfsson, Bharat Chandar, and Ruyu Chen