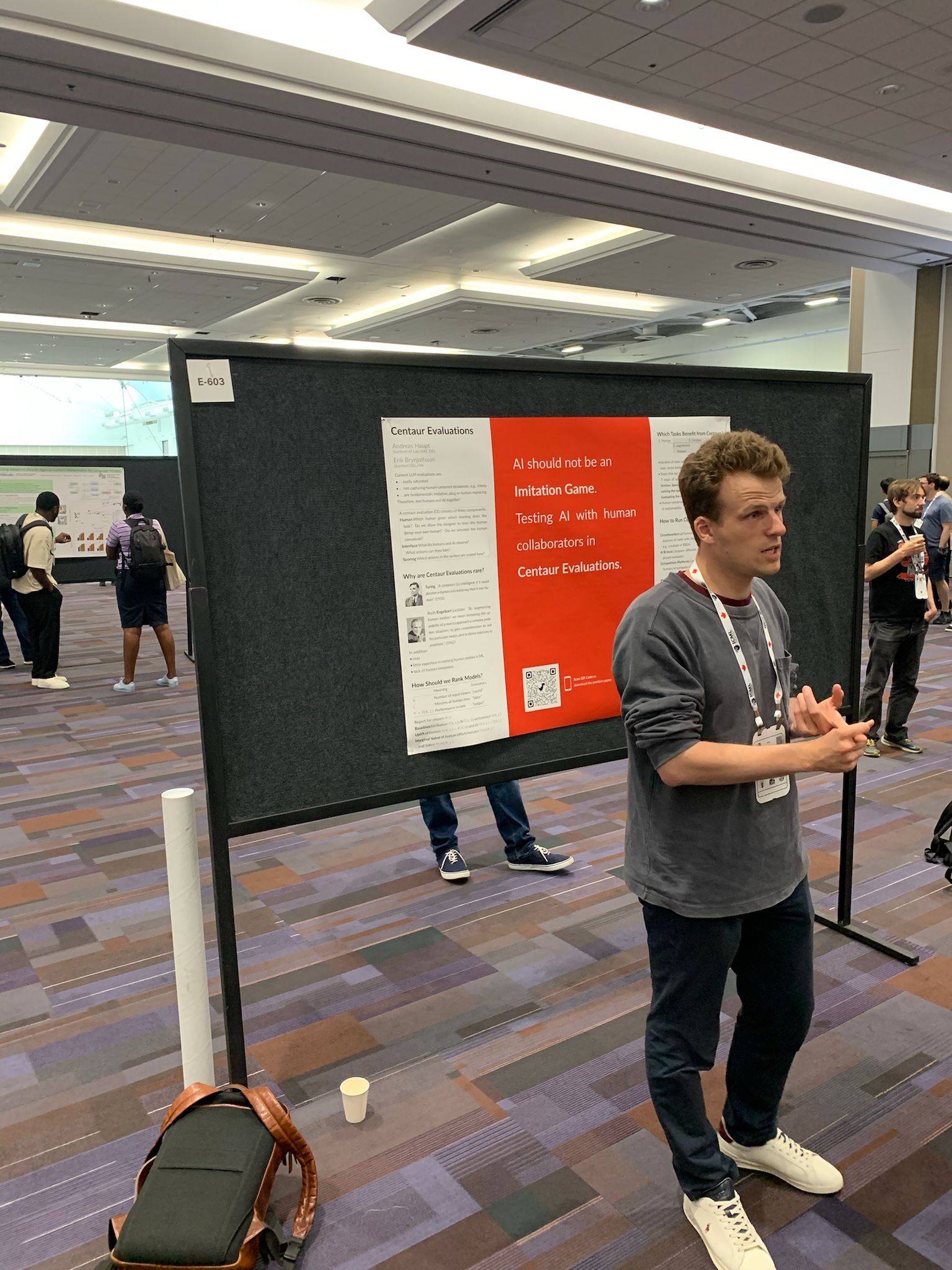

Centaur Evaluations

AI should not be an imitation game. It’s time to evaluate human-AI collaboration.

Why rethink AI evaluation?

Most popular AI benchmarks still test models in isolation: a model gets an input, produces an output, and earns a score without any human collaborator in the loop. That format is convenient, but it comes with three big blind spots.

- Many benchmarks saturate quickly: once models become very strong at exam-style question answering, the leaderboard stops distinguishing meaningful improvements.

- Benchmarks that omit humans struggle to capture human-centered desiderata such as interpretability, helpfulness, grounding, and the ability to work well with a user who asks follow-up questions or needs to check the output.

- Evaluation-by-imitation rewards systems that replace people rather than systems that reliably augment them.

Centaur Evaluations propose a different unit of measurement: the human + AI team. Instead of asking whether a model can imitate a human, we ask whether the model helps a human do the task better, faster, or more safely.

There’s such a long history on running randomized controlled trials in companies, and now everyone is evaluating AI. It felt too clear that we need to evaluate AI with the humans. That led to centaur evaluations.

What is a centaur evaluation?

A Centaur Evaluation (CE) is an evaluation design in which a human participant and an AI system jointly solve a task through an explicit interface and an explicit scoring rule. The core idea is to treat collaboration as the object of evaluation, not human replacement.

A Centaur Evaluation consists of three required components (and one optional component):

- Human: who participates, and what training is allowed (e.g., bring-your-own-human vs. crowd pool; or simulated humans).

- Interface: what the human and model can see and do; how collaboration and submissions work.

- Scoring: how outcomes (and possibly process/resources) are scored, including token and time budgets.

- Optional transcripts: interaction traces that help diagnose failure modes and teach better workflows.

Read the position paper

Why are centaur evaluations still rare?

Part of the answer is cultural. A long line of AI thinking, from the Turing Test onward, frames intelligence as a system’s ability to look human. If the goal is deception or indistinguishability, humans inside the loop can seem like a distraction.

But there is an equally strong tradition in computing that emphasizes augmentation: tools that amplify human capabilities rather than replace them. Centaur Evaluations align with this augmentation tradition, and they inherit its central question: what kinds of interfaces and division of labor make people more effective?

There are also practical barriers. Running human studies costs money and time, reproducibility is harder than in purely automated benchmarks, and many ML teams lack experience with experimental design. Finally, we do not yet have widely trusted ‘human simulators’ that could reduce the cost of prototyping centaur benchmarks without introducing a large simulation-to-reality gap.

If the thing we measure is how LLMs fare on human tasks, then we will improve them in doing human tasks, not in them working with humans. We self-inflict automation on our society unnecessarily.

How should we compare and rank models?

Centaur Evaluations make resource trade-offs explicit. Let K denote an input-token or compute budget (analogous to capital), L denote minutes of human time (analogous to labor), and let performance on the task be Y. For a given model i, the evaluation can be summarized by a centaur production function: Y = fᵢ(K, L).

| Symbol | Meaning | Economic analogy |

| K | Tokens / compute budget | Capital |

| L | Minutes of human time | Labor |

| Y = fᵢ(K, L) | Performance of the human-AI team | Output |

For a chosen operating point (K, L), a CE encourages reporting quantities that are directly interpretable for both model development and policy discussions:

- Baselines: human-only fᵢ(0, L), AI-only fᵢ(K, 0), and centaur fᵢ(K, L).

- Uplift: how much the human improves with AI assistance, and how much the AI improves with human involvement.

- Marginal value: the change in performance per additional minute of human time ∂fᵢ/∂L and per additional token ∂fᵢ/∂K.

Where do centaurs help the most?

Centaurs are especially useful when tasks naturally decompose into sub-steps that humans and models handle differently well. Think of workflows that mix research, judgment, drafting, verification, and communication. In such settings, the best system is often not the one that can imitate the entire workflow end-to-end, but the one that complements the user at the right moments.

They are also a good fit when success depends on human-centered constraints: oversight, trust, explanations that a user can act on, or grounding to the specific context in which a human is operating. These are exactly the properties that are difficult to infer from a static QA score but become measurable when a human must make decisions with the model’s help.

How to run Centaur Evaluations in practice

Centaur Evaluations do not require reinventing evaluation infrastructure. Three existing channels can support them:

Crowd work can recruit participants under controlled conditions, with standardized interfaces and token/time budgets. Deployed A/B tests can compare models in real workflows while logging outcomes and resource usage. And competition platforms can create leaderboards for human-AI teams, where shared transcripts reveal effective collaboration patterns and help both model builders and users learn.

A useful distinction is between ‘centaurized’ evaluations (existing benchmarks opened up to human-AI collaboration) and purpose-built centaur tasks designed around interaction and resource constraints from the start. The former lowers the barrier to entry; the latter can better reflect real-world work.

Project Status

Our own centaur evaluations are currently being prepared.

Researchers

Andy is a human-centered AI postdoctoral fellow jointly appointed in the Economics and Computer Science Departments.

He is very interested in the micro interactions of humans (in particular non-experts) with AI systems, and the implications for privacy, oversight, and consumer steering. At the lab, he specializes on evaluating humans and AI systems together. In his work, he develops and applies methods of microeconomic theory, structural econometrics, and reinforcement learning. He holds a Ph.D. from MIT in February 2025 with a committee evenly split between Economics and Computer Science. Prior to that, he completed two master’s degrees at the University of Bonn—first in Mathematics (2017) and then in Economics (2018), with distinction. He has worked on competition enforcement for the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Competition and the U.S. Federal Trade Commission, and taught high school mathematics and computer science in Germany before his Ph.D.

Read moreErik Brynjolfsson is one of the world’s leading experts on the economics of technology and artificial intelligence. He is the Jerry Yang and Akiko Yamazaki Professor and Senior Fellow at the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered AI (HAI), and Director of the Stanford Digital Economy Lab. He also is the Ralph Landau Senior Fellow at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR), Professor by Courtesy at the Stanford Graduate School of Business and Stanford Department of Economics, and a Research Associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

One of the most-cited authors on the economics of information, Brynjolfsson was among the first researchers to measure productivity contributions of IT and the complementary role of organizational capital and other intangibles.

Read more